The Ultimate Internet Mashup

June 3, 2006 4:07 PM Subscribe

Is "youtube" what the kids are calling wikipedia these days?

posted by Hildegarde at 4:29 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by Hildegarde at 4:29 PM on June 3, 2006

Huh? I don't get it. :scratches head:

posted by SenshiNeko at 4:38 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by SenshiNeko at 4:38 PM on June 3, 2006

Youtubepedia ?

posted by elpapacito at 4:48 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by elpapacito at 4:48 PM on June 3, 2006

False advertising is a serious crime, you sick bastard. I'm calling the police.

posted by stavrogin at 4:55 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by stavrogin at 4:55 PM on June 3, 2006

Hot town, Summa n' The City

Back of my neck getting dirty and gritty

Been down, isn't it a pity

Doesn't seem to be a shadow in the city

All around, people looking half dead

Walking on the sidewalk, hotter than a match head

But at night it's a different world

Go out and find a girl

Come-on come-on and dance all night

Despite the heat it'll be alright

And babe, don't you know it's a pity

That the days can't be like the nights

In the summa, in the city

In the summa, in the city

posted by ab3 at 4:55 PM on June 3, 2006

Back of my neck getting dirty and gritty

Been down, isn't it a pity

Doesn't seem to be a shadow in the city

All around, people looking half dead

Walking on the sidewalk, hotter than a match head

But at night it's a different world

Go out and find a girl

Come-on come-on and dance all night

Despite the heat it'll be alright

And babe, don't you know it's a pity

That the days can't be like the nights

In the summa, in the city

In the summa, in the city

posted by ab3 at 4:55 PM on June 3, 2006

Good God, did the Summa Theologica bore me to death. City of God didn't do much for me, either. I sort of liked Confessions, though. One guy in my seminar in college, though, just came alive during Aquinas. I decided he was peculiar.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 4:57 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 4:57 PM on June 3, 2006

you forgot the youtube links ... st augustine vs st thomas aquinas

no excuse, sgt serenity

posted by pyramid termite at 5:19 PM on June 3, 2006

no excuse, sgt serenity

posted by pyramid termite at 5:19 PM on June 3, 2006

St. Aug! Hells yeah!

posted by brundlefly at 5:38 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by brundlefly at 5:38 PM on June 3, 2006

The Summa Theologica was considered an authoritative compilation of the dogma of the Catholic Church, thus formed the basis for the Inquisition to determine heresy, which deviated from it.

posted by nickyskye at 5:52 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by nickyskye at 5:52 PM on June 3, 2006

I wrote this in another thread, but my sister, a minister, believes—and correctly, I think—that different people have different ways of coming to God. Some people are intuitive/emotional, some are intellectual. My own way of thinking about God and faith (though I'm an atheist) is a sort of combination of the mystical and intellectual. That's why Job and Matthew are my two favorite books of the Bible.

But Aquinas is, to my sensibilities, hyper-intellectual and absurdly so. I have the educational/intellectual background to understand the Scholastic theologians—I admire and am influenced by the Greeks as much as they are, I imagine—but it seems clear to me that the Scholastics, of whom Aquinas is the premier example, just went off the rails somewhere along the way.

More particularly, I believe very, very strongly in the utility of reason, but essential to that utility is to understand how to wield this tool and what its limitations are. A great many people in my estimation simply have very poor intuition about certain deep matters involving reason and thus misuse it. Aquinas, to me, demonstrates this exceedingly.

"How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?" is the cliched example with which we're all familiar; but in using an example which apparently involves a trivial subject matter, it neglects to call attention to how such misapplication and misuse of reason is frequently found in the context of asking very serious and important questions.

In my previous comment, I didn't mention Anselm, the first great Scholastic, and his Ontological Proof for the existence of God. Everytime I read it, even completely in context, I am just baffled how any intelligent person could fail to see the weaknesses in his argument. How could someone as apparently and earnesly rigorous as he not see where he went wrong? Similarly, there's the example of Pascal's Wager. That, too, is an example of very sloppy reasoning. How could he, and so many others, fail to realize this?

The answer, of course, is that despite any declarations from which we moderns might infer otherwise, these intellectuals were not anything at all like empiricists—an absurd comparison, I agree, but I mean this in one limited sense: they did not have a habit of mind that allows reason and experience to lead where they will—instead, like Plato, they were secure in their intuitive comprehension of what is True and for them reason was a means for describing a path for deducing what they already knew as True.

Anyway, Aquinas and the others bored me because right from the beginning, to my mind, they started off with absurdities and then just compounded them. All the while confidently using the language of reason. Ironically, the modern-day Objectivists/Randroids remind me of this—they start of with unexamined assumptions and use extraordinarily naive reasoning that is incomplete to reach conclusions they already hold, doing so with a great deal of ostentatious (apparent) rigor and not a little arrogance. I cringe at this sophomoric utilization of reason—a characterization that would be fighting words to the Scholastics, I'm sure.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 8:17 PM on June 3, 2006

But Aquinas is, to my sensibilities, hyper-intellectual and absurdly so. I have the educational/intellectual background to understand the Scholastic theologians—I admire and am influenced by the Greeks as much as they are, I imagine—but it seems clear to me that the Scholastics, of whom Aquinas is the premier example, just went off the rails somewhere along the way.

More particularly, I believe very, very strongly in the utility of reason, but essential to that utility is to understand how to wield this tool and what its limitations are. A great many people in my estimation simply have very poor intuition about certain deep matters involving reason and thus misuse it. Aquinas, to me, demonstrates this exceedingly.

"How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?" is the cliched example with which we're all familiar; but in using an example which apparently involves a trivial subject matter, it neglects to call attention to how such misapplication and misuse of reason is frequently found in the context of asking very serious and important questions.

In my previous comment, I didn't mention Anselm, the first great Scholastic, and his Ontological Proof for the existence of God. Everytime I read it, even completely in context, I am just baffled how any intelligent person could fail to see the weaknesses in his argument. How could someone as apparently and earnesly rigorous as he not see where he went wrong? Similarly, there's the example of Pascal's Wager. That, too, is an example of very sloppy reasoning. How could he, and so many others, fail to realize this?

The answer, of course, is that despite any declarations from which we moderns might infer otherwise, these intellectuals were not anything at all like empiricists—an absurd comparison, I agree, but I mean this in one limited sense: they did not have a habit of mind that allows reason and experience to lead where they will—instead, like Plato, they were secure in their intuitive comprehension of what is True and for them reason was a means for describing a path for deducing what they already knew as True.

Anyway, Aquinas and the others bored me because right from the beginning, to my mind, they started off with absurdities and then just compounded them. All the while confidently using the language of reason. Ironically, the modern-day Objectivists/Randroids remind me of this—they start of with unexamined assumptions and use extraordinarily naive reasoning that is incomplete to reach conclusions they already hold, doing so with a great deal of ostentatious (apparent) rigor and not a little arrogance. I cringe at this sophomoric utilization of reason—a characterization that would be fighting words to the Scholastics, I'm sure.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 8:17 PM on June 3, 2006

The great thing about Aquinas is that his use of reason is so good. His biggest fault came in relying on it instead of observation in many of his social commentaries (on women, slavery, etc.). You demand to ask, "Aquinas have you actually ever had any experience with any of these things?" Things that work for philosophy and theology don't necessarily work for anything else. Failure to recognize this is by far Aquinas' greatest fault.

posted by geoff. at 8:45 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by geoff. at 8:45 PM on June 3, 2006

Similarly, there's the example of Pascal's Wager. That, too, is an example of very sloppy reasoning. How could he, and so many others, fail to realize this?

let's examine that ...

------------------------------ there is a god-------------there is no god

believe in god .................... +50 ........................ 0

don't believe in god............ -50 ......................... 0

this looks something like the old "prisoner's dilemma" ... not that there's a logical justification for any of it, but the resemblance to game theory is interesting

posted by pyramid termite at 8:59 PM on June 3, 2006

let's examine that ...

------------------------------ there is a god-------------there is no god

believe in god .................... +50 ........................ 0

don't believe in god............ -50 ......................... 0

this looks something like the old "prisoner's dilemma" ... not that there's a logical justification for any of it, but the resemblance to game theory is interesting

posted by pyramid termite at 8:59 PM on June 3, 2006

instead, like Plato, they were secure in their intuitive comprehension of what is True and for them reason was a means for describing a path for deducing what they already knew as True

rereading some of aquinas' arguments makes me feel vaguely nostalgic, because like most students of logic and rhetoric, these were the arguments i cut my teeth on when first studying deductive reasoning. you hit on a couple of important points, ethereal bligh. even cartesian skepticism never completely avoids compounding certain absurdities, as you put it. and i think there are good reasons for that: deductive reasoning--even when complemented by inductive reasoning or empirical methodologies--always at some level relies on assumptions and postulates that require appeals to intuition. intuition, meanwhile, completely defies formal rigor.

i can remember back in college, i once took a class in philosophy of music that really drove this point home for me. our professor was lecturing on figurative representation in music. he played a simple piece meant to illustrate how instrumental music could be representational. i don't remember the name of the piece, and we weren't given the name of the piece in advance, but to my ear, it was clearly meant to sound like a steam locomotive. he asked the class what the music reminded them of. some correctly identified the music as sounding like a train, but to the obvious frustration of the professor (who'd meant this to be a simple example), the answers varied considerably, and even after we were finally told the name of the piece (which cinched the fact), fully a fourth of the class couldn't be persuaded it sounded like a train at all. Now, if some of the students were being intentionally obtuse or not, I can't say for sure, but at least a few of them genuinely didn't seem to see the resemblance. to me, that incident goes to the root of the whole problem.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:29 PM on June 3, 2006

rereading some of aquinas' arguments makes me feel vaguely nostalgic, because like most students of logic and rhetoric, these were the arguments i cut my teeth on when first studying deductive reasoning. you hit on a couple of important points, ethereal bligh. even cartesian skepticism never completely avoids compounding certain absurdities, as you put it. and i think there are good reasons for that: deductive reasoning--even when complemented by inductive reasoning or empirical methodologies--always at some level relies on assumptions and postulates that require appeals to intuition. intuition, meanwhile, completely defies formal rigor.

i can remember back in college, i once took a class in philosophy of music that really drove this point home for me. our professor was lecturing on figurative representation in music. he played a simple piece meant to illustrate how instrumental music could be representational. i don't remember the name of the piece, and we weren't given the name of the piece in advance, but to my ear, it was clearly meant to sound like a steam locomotive. he asked the class what the music reminded them of. some correctly identified the music as sounding like a train, but to the obvious frustration of the professor (who'd meant this to be a simple example), the answers varied considerably, and even after we were finally told the name of the piece (which cinched the fact), fully a fourth of the class couldn't be persuaded it sounded like a train at all. Now, if some of the students were being intentionally obtuse or not, I can't say for sure, but at least a few of them genuinely didn't seem to see the resemblance. to me, that incident goes to the root of the whole problem.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:29 PM on June 3, 2006

Pyramid: the problem with pascal's wager is that yahweh and satan might reserve particularly scenic portions of hell for pascal and anybody else fool enough to play that way.

You cannot pull a fast one on the man (or whatever) upstairs; salvation & damnation ain't that simple.

posted by bukvich at 10:02 PM on June 3, 2006

You cannot pull a fast one on the man (or whatever) upstairs; salvation & damnation ain't that simple.

posted by bukvich at 10:02 PM on June 3, 2006

eh? I thought the problem with Pascal's wager was that you have to bet on -which- God to believe in: the Pope's or Luther's.

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:41 PM on June 3, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:41 PM on June 3, 2006

sgt.serenity, I was curious about your take on your post. Was it to compare these two Christian thinkers who were influenced by Greek philosophers? I also wondered about the "hull" tag. Does that refer to the translator RFC Hull or something/somebody else? Could you clarify a little?

Aquinas epitomizes for me a lot of what is deeply dislikeable about Christianity, packed full of ugly and destructive hypocrisy on so many levels.

Human reason is so important to Aquinas but his beliefs were so unreasonable! He thought trade was ignoble but private property ok; he thought money was barren, simply invented for the purpose of exchange but also believed private possesion promoted a peaceful state, however people should not make profit! So how are people supposed to buy their possessions, no trades, no money made? It seems patently insane. He thought there should be a limited scope of government authority but the government should exterminate those who didn't believe specific Christian thoughts.

In regard to the assertions/points listed above:Notable points made by the Summa:

Theology is a science, the greatest of all the sciences, and the most certain (since its source is from God who knows everything).

As a non-theist, that statement seems transparently false to me.

"According to Aquinas, philosophy and theology do not contradict one another and play complementary roles in the quest for truth."

The existence of God, his total simplicity or lack of composition, his eternal nature ("eternal", in this case, means that he is altogether outside of time; time is held to be a part of the universe that God created), his knowledge, the way his will operates, and his power can all be proved by human reasoning alone, by anyone and at any time.

I wonder what he meant that God can be proved by anyone at any time?

Unbelief is the greatest sin in the realm of morals.

Presumably these are the grounds for the despicable sadism inflicted on 'heretics' that Aquinas (1225? – 1274 A.D.) set in motion, the Inquisition, which really was a holocaust that lasted centuries.

"On the part of the Church, however, there is mercy which looks to the conversion of the wanderer, wherefore she condemns not at once, but “after the first and second admonition,” as the Apostle directs: after that, if he is yet stubborn, the Church no longer hoping for his conversion, looks to the salvation of others, by excommunicating him and separating him from the Church, and furthermore delivers him to the secular tribunal to be exterminated thereby from the world by death (“Summa Theologica " by Thomas Aquinas, p. 150)"

The principles of Just War.

Right. The Christians have been so good at "just war". Not.

Defence lawyers cannot defend a person they know to be guilty.

I wonder how the Christian lawyers of the NACDL feel about that.

Taking interest on loans is forbidden, because it is charging people twice for the same thing.

Oh well, there go all the Christian bankers of the planet. What about the Vatican's gazillion dollar banking biz? "You can't run a church on Hail Mary's"

In and of itself, selling a thing for more or less than it is worth is unlawful (the just price theory).

No Christian capitalists then.

I liked Augustine better when he was a pagan Neoplatonic skeptic.

posted by nickyskye at 11:46 PM on June 3, 2006

Aquinas epitomizes for me a lot of what is deeply dislikeable about Christianity, packed full of ugly and destructive hypocrisy on so many levels.

Human reason is so important to Aquinas but his beliefs were so unreasonable! He thought trade was ignoble but private property ok; he thought money was barren, simply invented for the purpose of exchange but also believed private possesion promoted a peaceful state, however people should not make profit! So how are people supposed to buy their possessions, no trades, no money made? It seems patently insane. He thought there should be a limited scope of government authority but the government should exterminate those who didn't believe specific Christian thoughts.

In regard to the assertions/points listed above:Notable points made by the Summa:

Theology is a science, the greatest of all the sciences, and the most certain (since its source is from God who knows everything).

As a non-theist, that statement seems transparently false to me.

"According to Aquinas, philosophy and theology do not contradict one another and play complementary roles in the quest for truth."

The existence of God, his total simplicity or lack of composition, his eternal nature ("eternal", in this case, means that he is altogether outside of time; time is held to be a part of the universe that God created), his knowledge, the way his will operates, and his power can all be proved by human reasoning alone, by anyone and at any time.

I wonder what he meant that God can be proved by anyone at any time?

Unbelief is the greatest sin in the realm of morals.

Presumably these are the grounds for the despicable sadism inflicted on 'heretics' that Aquinas (1225? – 1274 A.D.) set in motion, the Inquisition, which really was a holocaust that lasted centuries.

"On the part of the Church, however, there is mercy which looks to the conversion of the wanderer, wherefore she condemns not at once, but “after the first and second admonition,” as the Apostle directs: after that, if he is yet stubborn, the Church no longer hoping for his conversion, looks to the salvation of others, by excommunicating him and separating him from the Church, and furthermore delivers him to the secular tribunal to be exterminated thereby from the world by death (“Summa Theologica " by Thomas Aquinas, p. 150)"

The principles of Just War.

Right. The Christians have been so good at "just war". Not.

Defence lawyers cannot defend a person they know to be guilty.

I wonder how the Christian lawyers of the NACDL feel about that.

Taking interest on loans is forbidden, because it is charging people twice for the same thing.

Oh well, there go all the Christian bankers of the planet. What about the Vatican's gazillion dollar banking biz? "You can't run a church on Hail Mary's"

In and of itself, selling a thing for more or less than it is worth is unlawful (the just price theory).

No Christian capitalists then.

I liked Augustine better when he was a pagan Neoplatonic skeptic.

posted by nickyskye at 11:46 PM on June 3, 2006

I thought Pascal's wager was more like this:

-----------------------------god exists ------- no god

believe in god ..............+∞ .................. 0

don't believe in god.......—∞ .................. 0

The fact that eternal salvation and eternal damnation are assigned infinite utilities is important, since it means that the probability of God's existance can be disregarded, however small, and it is still (supposedly) rational to believe in His existance.

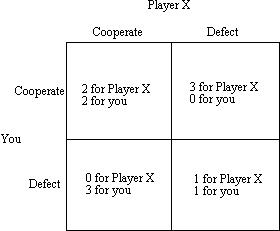

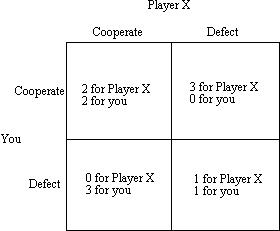

The Prisoners' Dilemma:

posted by matthewr at 1:13 AM on June 4, 2006

-----------------------------god exists ------- no god

believe in god ..............+∞ .................. 0

don't believe in god.......—∞ .................. 0

The fact that eternal salvation and eternal damnation are assigned infinite utilities is important, since it means that the probability of God's existance can be disregarded, however small, and it is still (supposedly) rational to believe in His existance.

The Prisoners' Dilemma:

posted by matthewr at 1:13 AM on June 4, 2006

pyramid termite: "this looks something like the old "prisoner's dilemma" ... not that there's a logical justification for any of it, but the resemblance to game theory is interesting"

I'd hesitate to call it "game theory", since as you described the problem there's only one player and two choices, so there's no interaction element—your outcome does not depend in any way on another's choices (unless you think of "nature" as a player choosing randomly between "a god exits" and "no god exists" or something along those lines). This is an elementary decision problem, and is not a prisoner's dilemma. The PD is characterized by the existence of a Pareto-dominant outcome (better for everyone) that is incentive incompatible for all players; that is, everyone would be better off if everyone cooperated, but each individual faces a decision in which he is individually better off by not cooperating, regardless of anyone else's decision.

The only similarity Pascal's wager bears to the PD is that there is a dominant strategy: believe in god. The resemblance ends there, though: there's no missed opportunity or foregone social improvement if everyone would reject the belief in god (er, well, there may be, but not as you described the choice).

matthewr: "The fact that eternal salvation and eternal damnation are assigned infinite utilities is important, since it means that the probability of God's existance can be disregarded, however small, and it is still (supposedly) rational to believe in His existance."

Actually, the probability of existence is immaterial, even in pyramid termite's set-up. For any probability between 0 and 1 (inclusive), belief is at least weakly dominant - that is, it's at least as good as non-belief.

Of course, others have pointed out a few basic reasons why Pascal's wager is nothing more than bad sophistry...

</derail>

posted by dilettanti at 9:31 AM on June 4, 2006

I'd hesitate to call it "game theory", since as you described the problem there's only one player and two choices, so there's no interaction element—your outcome does not depend in any way on another's choices (unless you think of "nature" as a player choosing randomly between "a god exits" and "no god exists" or something along those lines). This is an elementary decision problem, and is not a prisoner's dilemma. The PD is characterized by the existence of a Pareto-dominant outcome (better for everyone) that is incentive incompatible for all players; that is, everyone would be better off if everyone cooperated, but each individual faces a decision in which he is individually better off by not cooperating, regardless of anyone else's decision.

The only similarity Pascal's wager bears to the PD is that there is a dominant strategy: believe in god. The resemblance ends there, though: there's no missed opportunity or foregone social improvement if everyone would reject the belief in god (er, well, there may be, but not as you described the choice).

matthewr: "The fact that eternal salvation and eternal damnation are assigned infinite utilities is important, since it means that the probability of God's existance can be disregarded, however small, and it is still (supposedly) rational to believe in His existance."

Actually, the probability of existence is immaterial, even in pyramid termite's set-up. For any probability between 0 and 1 (inclusive), belief is at least weakly dominant - that is, it's at least as good as non-belief.

Of course, others have pointed out a few basic reasons why Pascal's wager is nothing more than bad sophistry...

</derail>

posted by dilettanti at 9:31 AM on June 4, 2006

The problem with Pascal's wager is that it doesn't take into account other religions.

posted by delmoi at 9:41 AM on June 4, 2006

posted by delmoi at 9:41 AM on June 4, 2006

Exactly. Even if we just take the three modern western religions (Judaism, Islam, and Christianity) into account we now have a much more complex system that the wager can survive in. Each of the three claims that it, and it alone, is the only true path to the theoretical ultimate reward. Now we have four choices: accept reality as it appears to be, or believe in one of three mutually exclusive belief systems in hopes that a) there is a god, and b) you've lucked into the right belief system. When your odds of getting the right system are 33%, the possible good outcome is so improbable, and the cost of going along with any of the three systems are factored in the wager stops seeming like a good deal.

Personally I've always rejected Pascal's wager for a more visceral reason. Any god who offers such little evidence for its existence as the Jewish/Christian/Muslim god does, but will torture you for all eternity if you don't believe in him is not a god I could ever worship, and if I did believe that such a god existed I would have no option but to hate him and do everything in my power to harm him.

The system of heaven, hell, and belief which is attributed to the Jewish/Christian/Muslim god is the most vile and despicable system I can envision and I have never understood how anyone could go along with it. You've lived a good life? Done your best to make the world a better place? Oops, sorry, you believed in the wrong god (or no god at all) you get tortured for all eternity. You've been a nasty little thug? No worries you believed in the right god, so welcome to heaven and enjoy the screams of the good people who held the wrong belief system echoing up from hell. Bugger that for a lark, and bugger any deity who would set up such an evil system. Its a good thing I'm an atheist, because if I wasn't I'd have to be a satanist....

posted by sotonohito at 11:54 AM on June 4, 2006

Personally I've always rejected Pascal's wager for a more visceral reason. Any god who offers such little evidence for its existence as the Jewish/Christian/Muslim god does, but will torture you for all eternity if you don't believe in him is not a god I could ever worship, and if I did believe that such a god existed I would have no option but to hate him and do everything in my power to harm him.

The system of heaven, hell, and belief which is attributed to the Jewish/Christian/Muslim god is the most vile and despicable system I can envision and I have never understood how anyone could go along with it. You've lived a good life? Done your best to make the world a better place? Oops, sorry, you believed in the wrong god (or no god at all) you get tortured for all eternity. You've been a nasty little thug? No worries you believed in the right god, so welcome to heaven and enjoy the screams of the good people who held the wrong belief system echoing up from hell. Bugger that for a lark, and bugger any deity who would set up such an evil system. Its a good thing I'm an atheist, because if I wasn't I'd have to be a satanist....

posted by sotonohito at 11:54 AM on June 4, 2006

These intellectuals were not anything at all like empiricists—an absurd comparison, I agree, but I mean this in one limited sense: they did not have a habit of mind that allows reason and experience to lead where they will—instead, like Plato, they were secure in their intuitive comprehension of what is True and for them reason was a means for describing a path for deducing what they already knew as True.

Anyway, Aquinas and the others bored me because right from the beginning, to my mind, they started off with absurdities and then just compounded them.

EB: You cannot let reason "lead where it will" - reason does not lead anywhere. Reason takes premises and churns out conclusions: that's all it does, and all it can do. It's direction is determined by your choice of premises - and these [first] premises cannot ultimately be determined by reason, because in order to derive a premise from reason, you must begin with a chain of reasoning that starts with a premise! So you either wind up with circular reasoning or with infinite regression. Thus, reason does not "lead where it will" - it's direction is determined by faith or intuition or some other form of knowledge which, taken in a single, indivisible package, is ultimately unreasonable. Unless you know, arationally, some fact which is True, you cannot begin to reason.

Experience, of course, can lead you where it will, but it is hard to see how experience, without reason to restrain it, could possibly be more trustworthy than intuition. In fact, aren't our intuitions often just a unconscious reaction to our experiences? Perhaps there is not even a difference.

In the end, when dealing with matters of ultimate concern, an "absurdity" is just a belief that you happen to find unappealing at an arational level. The Tao is vague, as some say.

posted by gd779 at 12:15 PM on June 4, 2006

Anyway, Aquinas and the others bored me because right from the beginning, to my mind, they started off with absurdities and then just compounded them.

EB: You cannot let reason "lead where it will" - reason does not lead anywhere. Reason takes premises and churns out conclusions: that's all it does, and all it can do. It's direction is determined by your choice of premises - and these [first] premises cannot ultimately be determined by reason, because in order to derive a premise from reason, you must begin with a chain of reasoning that starts with a premise! So you either wind up with circular reasoning or with infinite regression. Thus, reason does not "lead where it will" - it's direction is determined by faith or intuition or some other form of knowledge which, taken in a single, indivisible package, is ultimately unreasonable. Unless you know, arationally, some fact which is True, you cannot begin to reason.

Experience, of course, can lead you where it will, but it is hard to see how experience, without reason to restrain it, could possibly be more trustworthy than intuition. In fact, aren't our intuitions often just a unconscious reaction to our experiences? Perhaps there is not even a difference.

In the end, when dealing with matters of ultimate concern, an "absurdity" is just a belief that you happen to find unappealing at an arational level. The Tao is vague, as some say.

posted by gd779 at 12:15 PM on June 4, 2006

Notable points made by the Summa:

Theology is a science, the greatest of all the sciences, and the most certain (since its source is from God who knows everything).

Notable point made by anyone with a functioning brain: HAHAHAHAH learn to think, you retarded historical gimpwit.

In next week's exciting episode of "Ancient Arseclottery Falsely Dignified": prehistoric cave painter declares stick-figure artwork greatest thing since sliced bread. Whatever that is.

posted by Decani at 2:11 PM on June 4, 2006

Theology is a science, the greatest of all the sciences, and the most certain (since its source is from God who knows everything).

Notable point made by anyone with a functioning brain: HAHAHAHAH learn to think, you retarded historical gimpwit.

In next week's exciting episode of "Ancient Arseclottery Falsely Dignified": prehistoric cave painter declares stick-figure artwork greatest thing since sliced bread. Whatever that is.

posted by Decani at 2:11 PM on June 4, 2006

The problem with Pascal's wager is that belief in God, if God does not exist, very rarely results in zero net loss. It takes up an individual's time, attention, and money that could've been allocated elsewhere, and can cause that individual to make undesirable choices because their precepts are false. Therefore it can potentially represent a major negative utility to believe in God if God does not exist.

posted by ludwig_van at 4:28 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by ludwig_van at 4:28 PM on June 4, 2006

"You cannot let reason 'lead where it will' - reason does not lead anywhere."

Of course it does. But as to your main point—a reducto intended to demonstrate that my assertion was false—it's not a completely good-faith interpretation of my assertion. I would expect that you would be aware that I am aware that, strictly speaking, premises are not "rational" in the sense you describe. (You are equating reason with deduction which is not correct, however.) My point was that it is a matter of degree. I'm not really in the mood to engage you in your ultimate critique of reason.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 7:38 PM on June 4, 2006

Of course it does. But as to your main point—a reducto intended to demonstrate that my assertion was false—it's not a completely good-faith interpretation of my assertion. I would expect that you would be aware that I am aware that, strictly speaking, premises are not "rational" in the sense you describe. (You are equating reason with deduction which is not correct, however.) My point was that it is a matter of degree. I'm not really in the mood to engage you in your ultimate critique of reason.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 7:38 PM on June 4, 2006

"...reason does not lead anywhere."

"Of course it does."

Umm... where? By which I mean, what telos does reason supply? What is the (hehe) reason for reason, from reason's point of view?

posted by anotherpanacea at 7:49 PM on June 4, 2006

"Of course it does."

Umm... where? By which I mean, what telos does reason supply? What is the (hehe) reason for reason, from reason's point of view?

posted by anotherpanacea at 7:49 PM on June 4, 2006

Sorry, I turned down the job as Reason's spokesperson some time ago. :)

You guys are asking for some kind of absolutism which I can't provide, don't believe exists, and in any event have no interest in considering. I'm a pragmatist, I'm interested in utility. Thus my extreme impatience with Aquinas.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 8:16 PM on June 4, 2006

You guys are asking for some kind of absolutism which I can't provide, don't believe exists, and in any event have no interest in considering. I'm a pragmatist, I'm interested in utility. Thus my extreme impatience with Aquinas.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 8:16 PM on June 4, 2006

I'm not really in the mood to engage you in your ultimate critique of reason.

Well, that's quite all right. There's a time for discussion, but sometimes you're not in the mood. And, anyway, I wouldn't demand that you give me reasons for your belief in reason; if I'm right, that would be impossible.

On preview:

What is the (hehe) reason for reason, from reason's point of view?

Heh. Nice, anotherpanacea.

I'm a pragmatist, I'm interested in utility. Thus my extreme impatience with Aquinas.

But here you are doing precisely what you condemn Aquinas and Plato for doing: you are starting with what you know, before reason, to be True. Because, after all, your calculation of "utility" turns on your notion of what is "true" - if you had not felt from the beginning that Aquinas was very likely utterly wrong and "absurd", then you would no doubt have taken him more seriously; and you would have done so in the name of "utility". Aquinas no doubt considered himself eminently pragmatic - eternal salvation provides a great deal of utility, after all.

posted by gd779 at 8:37 PM on June 4, 2006

Well, that's quite all right. There's a time for discussion, but sometimes you're not in the mood. And, anyway, I wouldn't demand that you give me reasons for your belief in reason; if I'm right, that would be impossible.

On preview:

What is the (hehe) reason for reason, from reason's point of view?

Heh. Nice, anotherpanacea.

I'm a pragmatist, I'm interested in utility. Thus my extreme impatience with Aquinas.

But here you are doing precisely what you condemn Aquinas and Plato for doing: you are starting with what you know, before reason, to be True. Because, after all, your calculation of "utility" turns on your notion of what is "true" - if you had not felt from the beginning that Aquinas was very likely utterly wrong and "absurd", then you would no doubt have taken him more seriously; and you would have done so in the name of "utility". Aquinas no doubt considered himself eminently pragmatic - eternal salvation provides a great deal of utility, after all.

posted by gd779 at 8:37 PM on June 4, 2006

damn that formal incompleteness problem, eh eb? makes it possible to force anyone to some point that can't be formally justified. doesn't really prove anything about the subject matter of the argument though--it's just a formal trick, but it allows a skeptic to seemingly 'debunk' just about any philosophical position.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:02 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:02 PM on June 4, 2006

damn that formal incompleteness problem...

I think Aristotle, Hegel, and Heidegger all get this right (others too... but not Wittgenstein). Active nous, the circularity of absolute knowing, and the question of Being all express a "reasonable reason for reason," or at least a "logical logos of logos." The key is simply to find an entry (any entry) into the 'hermeneutic circle.' Once you're in, asking 'why' instead of 'how' or 'for the sake of what?' you're hooked. But the entry... that's gotta be what Aristotle calls wonder, thaumatzein. Something that just blows your socks off and makes you stop short and let an authentic thought in.

[Notes that we're in a scholastic thread] Umm... as for Augustine/Aquinas, I'm thinking that the problem comes when you short-circuit the revelation. When Augustine hears the child over the wall, (his formal conversion) he experiences this moment of wonder. But he immediately shortcircuits the wonder with a metaphysics he's derived from doctrine and a sort of half-baked Manicheanism. The ambit of reflection gets smaller and smaller, until thought just can't stand to stay within the limits of Christian theology. And thus, Spinoza is born.

posted by anotherpanacea at 9:24 PM on June 4, 2006

I think Aristotle, Hegel, and Heidegger all get this right (others too... but not Wittgenstein). Active nous, the circularity of absolute knowing, and the question of Being all express a "reasonable reason for reason," or at least a "logical logos of logos." The key is simply to find an entry (any entry) into the 'hermeneutic circle.' Once you're in, asking 'why' instead of 'how' or 'for the sake of what?' you're hooked. But the entry... that's gotta be what Aristotle calls wonder, thaumatzein. Something that just blows your socks off and makes you stop short and let an authentic thought in.

[Notes that we're in a scholastic thread] Umm... as for Augustine/Aquinas, I'm thinking that the problem comes when you short-circuit the revelation. When Augustine hears the child over the wall, (his formal conversion) he experiences this moment of wonder. But he immediately shortcircuits the wonder with a metaphysics he's derived from doctrine and a sort of half-baked Manicheanism. The ambit of reflection gets smaller and smaller, until thought just can't stand to stay within the limits of Christian theology. And thus, Spinoza is born.

posted by anotherpanacea at 9:24 PM on June 4, 2006

When Augustine hears the child over the wall, (his formal conversion) he experiences this moment of wonder. But he immediately shortcircuits the wonder with a metaphysics he's derived from doctrine and a sort of half-baked Manicheanism.

Wasn't it Augustine who described God, by way of an analogy to plane geometry, as a circle whose perimeter is nowhere and whose center is everywhere? I think it was, but please correct me if I'm wrong. Anyway, would that particular exercise in geometric visualization qualify as a genuine "moment of wonder"? Because once I figured out that the old magic circle image was an attempt to grapple with the logical consequences of projecting the perimeter of a circle to infinity, I was kind of awestruck.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:51 PM on June 4, 2006

Wasn't it Augustine who described God, by way of an analogy to plane geometry, as a circle whose perimeter is nowhere and whose center is everywhere? I think it was, but please correct me if I'm wrong. Anyway, would that particular exercise in geometric visualization qualify as a genuine "moment of wonder"? Because once I figured out that the old magic circle image was an attempt to grapple with the logical consequences of projecting the perimeter of a circle to infinity, I was kind of awestruck.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 9:51 PM on June 4, 2006

actually, it looks like it was pascal.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:22 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:22 PM on June 4, 2006

or maybe it was Plotinus... apparently, there's some controversy over who originated the idea.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:25 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:25 PM on June 4, 2006

Augustine did used that particular trope as an analogy for God, but I believe it goes back to the Pythagoreans. History of geometry is far from my specialty, though.

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:27 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:27 PM on June 4, 2006

Actually, googling about a bit, it looks like Emerson said he used it (in "Circles," which was the essay I was thinking of when I wrote my comment) but there doesn't seem to be any textual evidence to back that up. It sort of sounds a little off for him: he was a rhetorician, not a geometer, so he would only have used it in that far-out freaky way that pot-heads talk about transinfinites and quantum physics. On the other hand, he had a little of the stoner-dude in him, so I won't be surprised if someone comes up with the reference.

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:37 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 10:37 PM on June 4, 2006

he was a rhetorician, not a geometer, so he would only have used it in that far-out freaky way that pot-heads talk about transinfinites and quantum physics.

funny you say that, because i had always heard this analogy used in exactly that sort of quasi-mystical, barely-comprehensible way your talking about and just dismissed it as mumbo-jumbo. then i thought about it a second longer and realized it was just a plain language description of an exercise in what we would now call projective geometry i was pretty impressed.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:53 PM on June 4, 2006

funny you say that, because i had always heard this analogy used in exactly that sort of quasi-mystical, barely-comprehensible way your talking about and just dismissed it as mumbo-jumbo. then i thought about it a second longer and realized it was just a plain language description of an exercise in what we would now call projective geometry i was pretty impressed.

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:53 PM on June 4, 2006

('AND i was pretty impressed,' i mean.)

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:54 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:54 PM on June 4, 2006

(and we'll just let the other typos slide...)

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:56 PM on June 4, 2006

posted by all-seeing eye dog at 10:56 PM on June 4, 2006

"damn that formal incompleteness problem, eh eb? makes it possible to force anyone to some point that can't be formally justified. doesn't really prove anything about the subject matter of the argument though--it's just a formal trick, but it allows a skeptic to seemingly 'debunk' just about any philosophical position."

Yes. But what I've never understood is how people conveniently distinguish between so-called "reason" and reasonable discourse. They'll use reasonable discourse to attempt to critique reason, and I don't know what they think they've proven. You have all these people who are self-proclaimed relativists who every day and in so many discussions take implied absolutist positions.

There are things that can be talked about and things that cannot. If "your" (not you personally) argument includes an assumption that the subject of the argument can't be talked about, then why am I under any obligation to participate? I have better things to do.

For me it's ironic that gd779 aludes to the Tao because my imperfect, Western comprehension of the Tao paints a picture that is very appealing to me and which is opposed to the spirit of gd779's argument. If you want an aggressive relativism, a denial, an attack on reason, then ambrace Zen, which I personally think is precisely aimed as a corrective for those who need it. But Taoism is pragmatic, it lets things be what they are. It certainly isn't hostile to reason, at least in the opinion of the pretty well-regarded Taoist and logician Raymond Smullyan.

As I say in the previous paragraph, I believe that Zen exists as a corrective to those who would otherwise be so seduced by reason that they would become what in our time and culture are familiar with as Objectivists. Naive rationalists. But if I ever was a naive rationalist, I didn't remain one long past my adolescence, and I'm middle-aged today. A Zen Buddhist may wonder, before he/she steps through the door, whether the door really exists. A Taoist may also wonder, but not to the point of indecision and certainly not to the point that he/she insists everyone ought to learn to walk through walls. Besides, he/she is hungry and it's time for dinner.

This whole class of self-referential problems within the context of rational comprehension is very interesting and provocative. I've long ago learned to be cautious with them and particularly in the case of Godel Incompleteness I tend to warn other people against generalizing from it. But if nothing else, this class of problems pounds into our heads that there are limits to the sort of comprehension to which we naturally aspire. That there are limits in no way demonstrate that this sort of comprehension is impossible or useless, but it acts as an important check against our instinct to the solispistic hubris of holding the entire cosmos within ourselves.

Implicitly, the disregard for those limits upon reason is an example of the category error. And the category error abounds. Either a relentless reductionism or a relentless holism are category errors because they are both universalist—everything is supposed to be directly comprehensible in relationship to everything else. But why? Because we want it do be this way? We need it do be?

And while it's necessary to assume that something is comprehensible, at least on the level of the mundane practice of our lives, it certainly isn't necessary to assume that everything is comprehensible.

All this is deeply related to why I find Matthew appealing and why I characterize its presentation of Christian faith as intellectual/mystical. Within the context of Faith, those like Aquinas are the equivalent to the type that I characterized as Objectivists above. Those who see no limit to reason are those for whom mysticism and/or unreason are a much-needed corrective. Why do you use words to make me understand but choose words that confuse? Because confusion is necessary—at least for some.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 12:15 AM on June 5, 2006

Yes. But what I've never understood is how people conveniently distinguish between so-called "reason" and reasonable discourse. They'll use reasonable discourse to attempt to critique reason, and I don't know what they think they've proven. You have all these people who are self-proclaimed relativists who every day and in so many discussions take implied absolutist positions.

There are things that can be talked about and things that cannot. If "your" (not you personally) argument includes an assumption that the subject of the argument can't be talked about, then why am I under any obligation to participate? I have better things to do.

For me it's ironic that gd779 aludes to the Tao because my imperfect, Western comprehension of the Tao paints a picture that is very appealing to me and which is opposed to the spirit of gd779's argument. If you want an aggressive relativism, a denial, an attack on reason, then ambrace Zen, which I personally think is precisely aimed as a corrective for those who need it. But Taoism is pragmatic, it lets things be what they are. It certainly isn't hostile to reason, at least in the opinion of the pretty well-regarded Taoist and logician Raymond Smullyan.

As I say in the previous paragraph, I believe that Zen exists as a corrective to those who would otherwise be so seduced by reason that they would become what in our time and culture are familiar with as Objectivists. Naive rationalists. But if I ever was a naive rationalist, I didn't remain one long past my adolescence, and I'm middle-aged today. A Zen Buddhist may wonder, before he/she steps through the door, whether the door really exists. A Taoist may also wonder, but not to the point of indecision and certainly not to the point that he/she insists everyone ought to learn to walk through walls. Besides, he/she is hungry and it's time for dinner.

This whole class of self-referential problems within the context of rational comprehension is very interesting and provocative. I've long ago learned to be cautious with them and particularly in the case of Godel Incompleteness I tend to warn other people against generalizing from it. But if nothing else, this class of problems pounds into our heads that there are limits to the sort of comprehension to which we naturally aspire. That there are limits in no way demonstrate that this sort of comprehension is impossible or useless, but it acts as an important check against our instinct to the solispistic hubris of holding the entire cosmos within ourselves.

Implicitly, the disregard for those limits upon reason is an example of the category error. And the category error abounds. Either a relentless reductionism or a relentless holism are category errors because they are both universalist—everything is supposed to be directly comprehensible in relationship to everything else. But why? Because we want it do be this way? We need it do be?

And while it's necessary to assume that something is comprehensible, at least on the level of the mundane practice of our lives, it certainly isn't necessary to assume that everything is comprehensible.

All this is deeply related to why I find Matthew appealing and why I characterize its presentation of Christian faith as intellectual/mystical. Within the context of Faith, those like Aquinas are the equivalent to the type that I characterized as Objectivists above. Those who see no limit to reason are those for whom mysticism and/or unreason are a much-needed corrective. Why do you use words to make me understand but choose words that confuse? Because confusion is necessary—at least for some.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 12:15 AM on June 5, 2006

EB, I think you are making the common mistake of regarding Aquinas as a dogmatic theologian, who starts off with a set of propositions about God, the Church, etc etc, and then uses the tools of reason and philosophy to justify them. That, if I may say so, is a complete misunderstanding of what Aquinas is all about. He is, for me, a negative theologian, who takes the tools of reason and philosophy and uses them to destroy a whole lot of assumptions about the nature of God.

I can't accept your view of Aquinas as an extreme rationalist -- one who, in your words, sees 'no limit to reason'. Indeed, I don't see how anyone who has made the slightest attempt to engage with Aquinas's ideas could possibly hold that view. Of course Aquinas sees limits to reason! Yes, he believes that theology can and should be examined in the light of natural reason (we don't just have to take it 'on faith'), but he believes that by doing so, we will come to realise that reason has its limits, and that it points beyond itself to God's self-revelation.

(Let me make it clear that I am not trying to 'defend' Aquinas, or to engage in any kind of Christian apologetic. I am simply trying to point out where you have misunderstood Aquinas, and to correct your bizarre misreading of him as a sort of Christian Objectivist.)

Please do not take this as any kind of personal attack. (I read Godel, Escher. Bach as a teenager, and it had a profound effect on me -- so I can see where you are coming from, with your remarks about Zen and self-referential problems, and I am very sympathetic to that way of thinking.) But when it comes to Aquinas, I'm afraid you were badly taught in your college seminar. You need to jettison everything you think you know about Aquinas, and start again, preferably by reading one of his modern interpreters, such as Herbert McCabe, who can show you how Aquinas differs from the later scholastic tradition.

posted by verstegan at 1:30 AM on June 5, 2006

I can't accept your view of Aquinas as an extreme rationalist -- one who, in your words, sees 'no limit to reason'. Indeed, I don't see how anyone who has made the slightest attempt to engage with Aquinas's ideas could possibly hold that view. Of course Aquinas sees limits to reason! Yes, he believes that theology can and should be examined in the light of natural reason (we don't just have to take it 'on faith'), but he believes that by doing so, we will come to realise that reason has its limits, and that it points beyond itself to God's self-revelation.

(Let me make it clear that I am not trying to 'defend' Aquinas, or to engage in any kind of Christian apologetic. I am simply trying to point out where you have misunderstood Aquinas, and to correct your bizarre misreading of him as a sort of Christian Objectivist.)

Please do not take this as any kind of personal attack. (I read Godel, Escher. Bach as a teenager, and it had a profound effect on me -- so I can see where you are coming from, with your remarks about Zen and self-referential problems, and I am very sympathetic to that way of thinking.) But when it comes to Aquinas, I'm afraid you were badly taught in your college seminar. You need to jettison everything you think you know about Aquinas, and start again, preferably by reading one of his modern interpreters, such as Herbert McCabe, who can show you how Aquinas differs from the later scholastic tradition.

posted by verstegan at 1:30 AM on June 5, 2006

Does that refer to the translator RFC Hull or something/somebody else? Could you clarify a little?

God herself cannot fathom the sgt.'s love of Hull. Consider the hull tag, if you dare.

posted by jack_mo at 5:25 AM on June 5, 2006

God herself cannot fathom the sgt.'s love of Hull. Consider the hull tag, if you dare.

posted by jack_mo at 5:25 AM on June 5, 2006

"But when it comes to Aquinas, I'm afraid you were badly taught in your college seminar."

I wasn't taught any interpretation of Aquinas—moreover, since I found him distasteful and boring, my impression is not greatly considered or reliable. On the other hand, I'm more than a little skeptical of an attempt to redefine Aquinas as something other than the epitome of the Scholastics—that has the sound of someone's pet theory.

What I saw was an excessive and frequent misapplication of reason...a widely agreed upon characteristic of the Scholastics. I appreciate your critique and doubly appreciate the reminder that my comprehension of Aquinas is more likely than not to be flawed (because of my distaste), and I'll keep that in mind should I ever feel it my duty to pick him up again and give him another chance.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 6:52 AM on June 5, 2006

I wasn't taught any interpretation of Aquinas—moreover, since I found him distasteful and boring, my impression is not greatly considered or reliable. On the other hand, I'm more than a little skeptical of an attempt to redefine Aquinas as something other than the epitome of the Scholastics—that has the sound of someone's pet theory.

What I saw was an excessive and frequent misapplication of reason...a widely agreed upon characteristic of the Scholastics. I appreciate your critique and doubly appreciate the reminder that my comprehension of Aquinas is more likely than not to be flawed (because of my distaste), and I'll keep that in mind should I ever feel it my duty to pick him up again and give him another chance.

posted by Ethereal Bligh at 6:52 AM on June 5, 2006

To anyone trying to grok the beautiful Thomist worldview, I highly recommend Jacques Maritain's Preface to Metaphysics.

From Wikipedia: in light of attaining being reflexively through apprehension of sense experience one may arrive at what Maritain calls "an Intuition of Being". For Maritian this is point of departure for metaphysics, without the intuition of being one cannot be a metaphysician at all.

posted by sonofsamiam at 7:17 AM on June 5, 2006

From Wikipedia: in light of attaining being reflexively through apprehension of sense experience one may arrive at what Maritain calls "an Intuition of Being". For Maritian this is point of departure for metaphysics, without the intuition of being one cannot be a metaphysician at all.

posted by sonofsamiam at 7:17 AM on June 5, 2006

For latter-day Augustinians, check out Jean-Louis Chretien's The Unforgettable and the Unhoped For. Amazon.

posted by anotherpanacea at 9:12 AM on June 5, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 9:12 AM on June 5, 2006

Aquinas’ last work was his best, and really the only true one.

posted by Smedleyman at 10:06 AM on June 5, 2006

posted by Smedleyman at 10:06 AM on June 5, 2006

Eh? His commentary on Aristotle's On Generation and Corruption? Or the Compendium of Theology?

posted by anotherpanacea at 11:01 AM on June 5, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 11:01 AM on June 5, 2006

anotherpanacea - His silence.

He stopped writing in the middle of the Sacrament of Penance.

Aquinas’ comment to Reginald of Piperno:

“All that I have hitherto written seems to me nothing but straw.”

/It’s a hard concept to relate through this medium. But there is an apprehension that cannot be expressed by thought or speech. And that’s what he was conveying. Plenty of commentary on the silence of Aquinas. Some of the less dogmatic interpretations aren’t bad.

posted by Smedleyman at 12:33 PM on June 5, 2006

He stopped writing in the middle of the Sacrament of Penance.

Aquinas’ comment to Reginald of Piperno:

“All that I have hitherto written seems to me nothing but straw.”

/It’s a hard concept to relate through this medium. But there is an apprehension that cannot be expressed by thought or speech. And that’s what he was conveying. Plenty of commentary on the silence of Aquinas. Some of the less dogmatic interpretations aren’t bad.

posted by Smedleyman at 12:33 PM on June 5, 2006

.

posted by anotherpanacea at 12:50 PM on June 5, 2006

posted by anotherpanacea at 12:50 PM on June 5, 2006

*smile*

posted by Smedleyman at 12:58 PM on June 5, 2006

posted by Smedleyman at 12:58 PM on June 5, 2006

God herself cannot fathom the sgt.'s love of Hull. Consider the hull tag, if you dare.

ROFL, thanks jack_mo for the first real bellylaugh of my day.

What is it with the the sgt. and "hull"?

posted by nickyskye at 5:33 PM on June 5, 2006

ROFL, thanks jack_mo for the first real bellylaugh of my day.

What is it with the the sgt. and "hull"?

posted by nickyskye at 5:33 PM on June 5, 2006

« Older The Fizzmaker | Forever Pregnant II: Morality Boogaloo Newer »

This thread has been archived and is closed to new comments

Theology is a science, the greatest of all the sciences, and the most certain (since its source is from God who knows everything). [1]

The existence of God, his total simplicity or lack of composition, his eternal nature ("eternal", in this case, means that he is altogether outside of time; time is held to be a part of the universe that God created), his knowledge, the way his will operates, and his power can all be proved by human reasoning alone, by anyone and at any time.

Unbelief is the greatest sin in the realm of morals. [2]

The principles of Just War.

Defence lawyers cannot defend a person they know to be guilty.

Taking interest on loans is forbidden, because it is charging people twice for the same thing.

In and of itself, selling a thing for more or less than it is worth is unlawful (the just price theory).

posted by sgt.serenity at 4:10 PM on June 3, 2006